In one of the city’s most prestigious neighborhoods, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 79th Street—right across from Central Park and next to the Metropolitan Museum of Art—stands a mansion that manages to outshine even its equally distinguished neighbors with its grandeur and opulent exterior.

This residence, a striking monument of New York’s “Gilded Age,” carries the address 📍2 East 79th Street and is known as the Harry F. Sinclair House—or, by its current occupant, the Ukrainian Institute of America.

History and Architecture of the Ukrainian Institute of America House

The project was designed by architect Charles P. H. Gilbert, a master whose houses defined the Upper East Side in the late 19th century. Among his works are the building now housing the Polish Consulate in New York (Joseph Raphael De Lamar House), Cartier’s Fifth Avenue flagship (Cartier Building), and the Austrian Consulate. Gilbert also worked on the Henry Clay Frick House (today’s Frick Collection) and the Felix M. Warburg House (now the Jewish Museum)

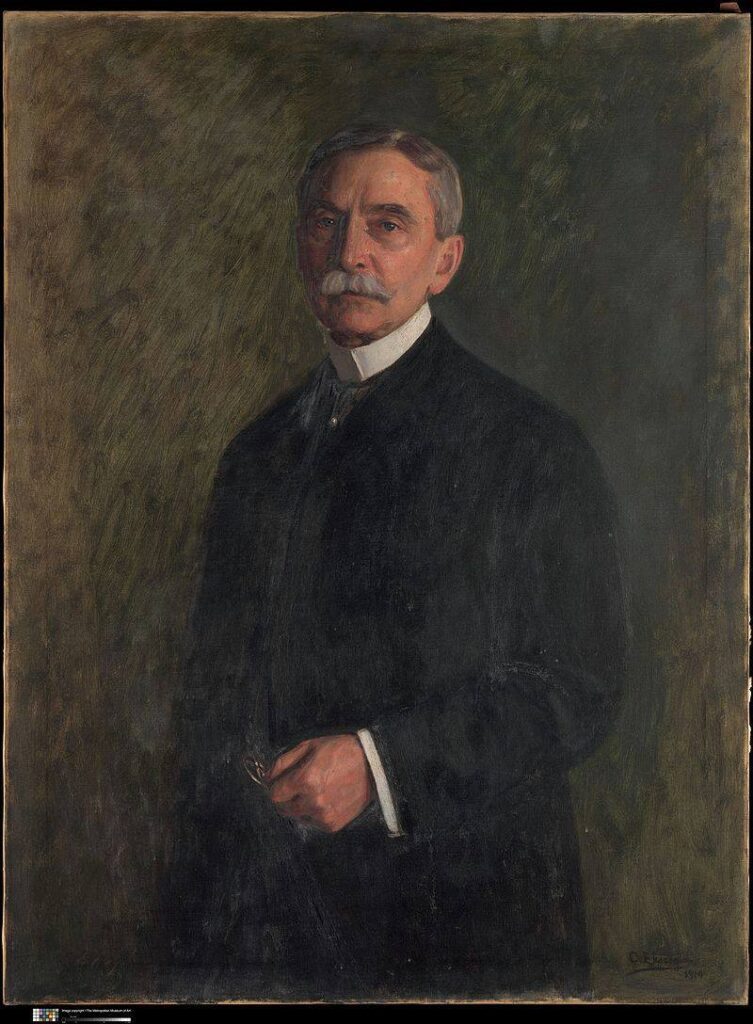

Built between 1897 and 1899 for industrialist and art collector Isaac Fletcher, the house is a showcase of eclectic French Renaissance style: gray limestone facades, copper-roofed turrets, ornate gables, and huge windows overlooking the park.

Inside, it was nothing short of a palace: 27 rooms across six floors, covering nearly 20,000 square feet. At one time it featured a ballroom, library, grand staircases, fireplaces, and service quarters connected by hidden passageways.

Fletcher, who made his fortune in metallurgy and banking, served as president of the Corn Exchange Bank and was a leading figure in New York’s business world at the turn of the century. He amassed a significant collection of European paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts, including works by Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Gainsborough, and others.

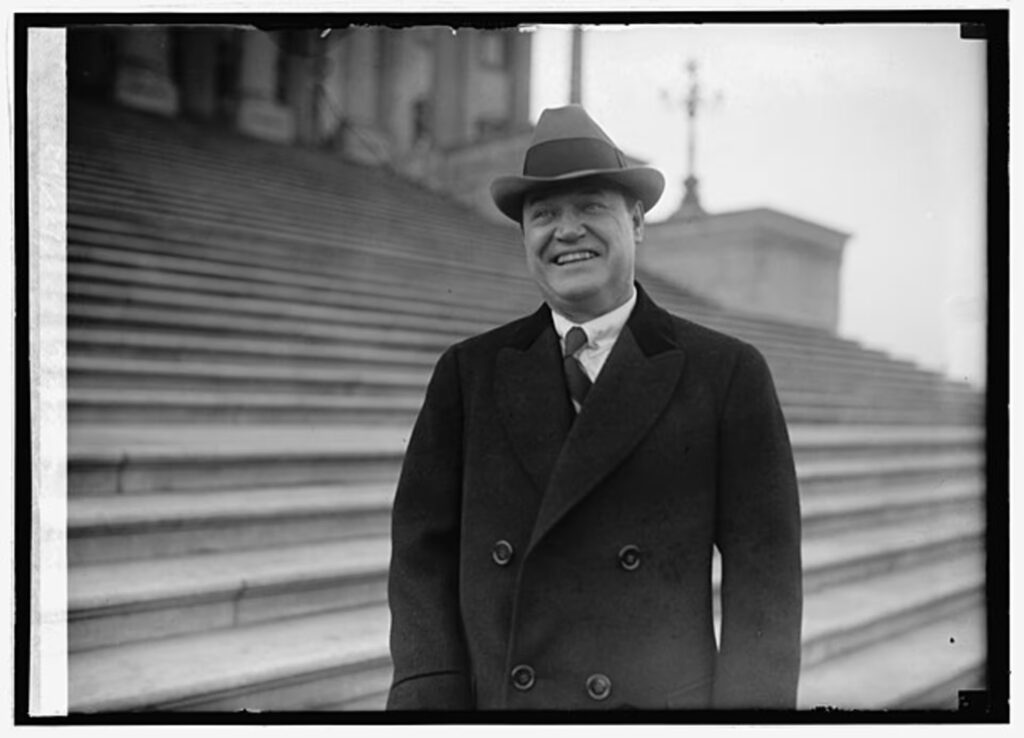

After Fletcher’s death, the house and his entire estate were bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. However, the Met was unable to find a suitable use for the mansion and sold it in 1918 to oil tycoon Harry Sinclair—later infamous for his role in the Teapot Dome scandal, one of the largest political scandals in U.S. history.

In 1930, burdened by debt, Sinclair sold the mansion to Augustus and Anne van Horne Stuyvesant, the last direct descendants of Peter Stuyvesant, the final Dutch governor of New Netherland. The siblings lived in the mansion until their deaths in 1953 and 1938, respectively.

The Teapot Dome Scandal

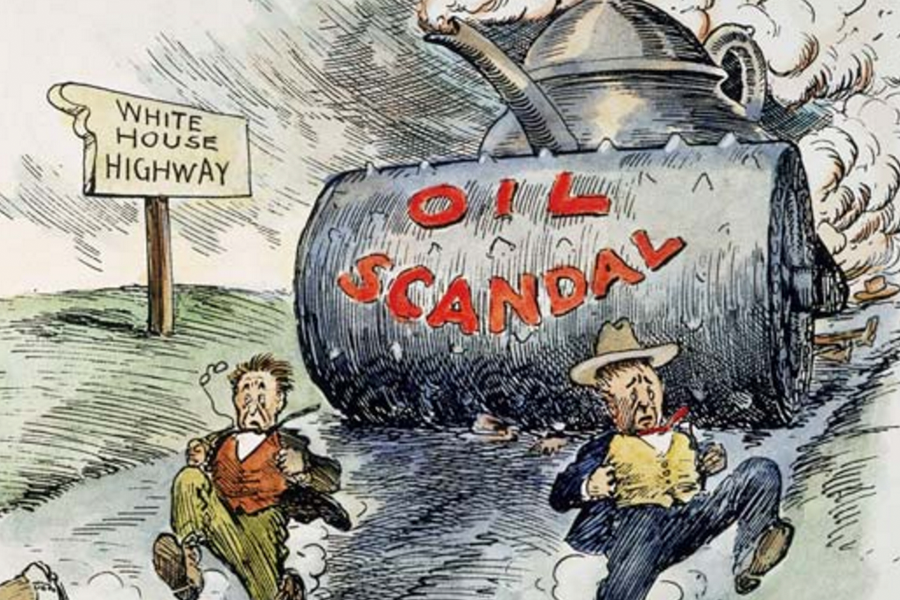

The scandal takes its name from 📍Teapot Dome, Wyoming, where one of three strategic oil reserves reserved for the U.S. Navy was located.

In the early 20th century, the Navy was rapidly switching from coal to oil. To secure wartime supplies, Congress placed key reserves under naval control.

But in 1921, President Warren Harding transferred oversight of the reserves from the Navy to the Department of the Interior. Its secretary, Albert Fall—a Harding crony—secretly leased the fields without competitive bidding to oil barons, including Harry Sinclair.

It later emerged that Fall had received about $400,000 (over $7 million today) in “loans” and “gifts” from Sinclair and others, including cash, bonds, and debt repayments. A Senate investigation backed by the press exposed the corruption. In 1927, the Supreme Court voided the leases.

By 1929, Fall became the first U.S. cabinet member ever convicted of corruption, sentenced to one year in prison and fined $100,000. For decades, Teapot Dome was shorthand for government corruption—until Watergate eclipsed it.

The Ukrainian Chapter

In 1954, the Stuyvesant estate sold the house to investors, who soon auctioned it. In 1955, it was purchased by William Dzus, a Ukrainian-born American engineer and entrepreneur who made a fortune inventing self-locking fasteners for aviation. By then, Dzus had already founded (in 1948) the Ukrainian Institute of America (UIA), a nonprofit dedicated to promoting Ukrainian culture. The long-vacant mansion gained new life as its headquarters.

In Cold War New York, the UIA, together with the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences, university Slavic departments, and broadcasters like Radio Liberty and Voice of America, worked to raise Ukraine’s international profile while it remained under Soviet rule.

To this day, the UIA preserves the mansion much as it was when the Fletcher family moved in—interiors remain largely untouched. Open to the public, its stately yet inviting rooms have hosted hundreds of cultural events uniting Ukrainians and Americans alike: art exhibitions, concerts, film screenings, poetry readings, literary evenings, children’s programs, lectures, symposia, and receptions.

Unlike many cultural institutions limited to galleries, consulates, or private clubs, the UIA blends all these roles—while remaining accessible to the broader public, not just the Ukrainian diaspora.

The Story of William Dzus

William Dzus (Volodymyr Dzhus) is a remarkable example of how a talented immigrant transformed an industry while leaving a lasting cultural legacy in New York.

Born in 1895, Dzus immigrated to the U.S. in 1913 and settled in New York. He first worked as a machinist, then opened a small auto repair shop in West Islip. In his garage, he invented the vibration-resistant self-locking fastener—an innovation that revolutionized aviation. By 1932 he founded the Dzus Fastener Company.

By 1938 the company had its own building at 📍425 Union Boulevard, and by 1943 it employed 600 people.

Dzus fasteners soon spread far beyond aviation—to motorsports, shipbuilding, trucks, buses, electronics, rockets, and even orthopedic surgery. Their unique feature: unlike threaded fasteners, they tightened under stress rather than loosened, making them ideal for panels, doors, and covers requiring frequent removal.

In 1948 Dzus founded the Ukrainian Institute of America and served as its president. He remained head of his company until his death in 1964, after which leadership passed to his son Theodore, and later his grandson Theodore Jr. Under their management, the company expanded internationally, opening branches in Germany, Japan, Scotland, and France, and diversifying into aerospace, refrigeration, and electronics. Eventually, the company was sold to DFCI Solutions, and later to the global corporation Southco, which owns it to this day.